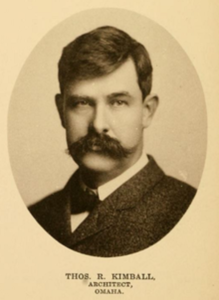

The Architect: Thomas Rogers Kimball

Thomas Rogers Kimball had 871 commissions spanning several states. He was perhaps Nebraska's most distinguished and influential architect.

He was born in Linwood, a suburb of Cincinnati, Ohio, on April 19, 1862. His father brought the family to Omaha in 1871 where he served as a vice-president of the Union Pacific Railroad. As a youngster, he lived in the pleasant Park Wilde neighborhood south of downtown and attended the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. From 1883-86 he studied painting at the Cowles School of Art in Boston and attended classes at America's first school of architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating in 1886.

In 1890 Kimball became a student at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris. The Ecole was intensely competitive, and had a rigid, demanding curriculum. The students had to master the principles of design used by the ancient Greeks and Romans and became masters of all elements of architecture used by other European builders. The goals were rationality, harmony, dignity and good taste; Kimball had numerous opportunities through lectures and travels on the continent to become a master of these. In Paris he became a superb water-colorist studying under Harpignies and Vignal, two of France's most acclaimed artists.

Returning to America, he worked as an architect in Boston with C. Howard Walker, before coming with Walker to Omaha. During 1891-92, when local entrepreneur Byron Reed made a large donation to the city for a major library building to be erected at Nineteenth and Harney Streets, Kimball was named the architect. No longer a library, the building stands today, and its formal grandeur shows the historical knowledge and exact instinct for pleasing proportion that Kimball would bring to the design of Saint Cecilia Cathedral.

Omaha was determined to make the city a fit place for the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898, and Kimball was given the responsibility for the overall design--a smaller but equally magnificent version of the Chicago World's Fair of a few years earlier--he also created the Late Greek Revival design for the Burlington Railroad Station on Tenth Street, where so many fair-goers would arrive.

Quickly Kimball started getting commissions for every kind of building--Gold Coast mansions for the Gallaghers, Kirkendalls, Wattles, and other prominent families; massive warehouses in the district known as Jobbers' Canyon (the Nash Building became the local headquarters for McKesson and Robbins and later the Greenhouse Apartments); more churches in historic styles, like St. Francis Cabrini Catholic Church and the old All Saints Episcopal; an addition to Duchesne Academy, the impressive Fontenelle Hotel, the Medical Arts Building, and banks, more libraries, more mansions, and schools. Of course, Saint Cecilia Cathedral is his masterpiece.

The Cathedral's Renaissance Revival style seems to have been an entirely fitting choice for an architect with a reputation as something of a "Renaissance man." A 1934 address delivered by William Steele, Thomas Rogers Kimball's architect-partner, reads "that he had so many interests that he always gave the impression of being in a hurry." This sentiment is echoed in a resolution adopted by the Omaha Chapter of the American Inter-Professional Institute which said posthumously of Kimball that "He drank deeply and courageously of life. His tastes were catholic [sic], his interests comprehensive, his sympathies broad and genuine." Kimball's architectural legacy is reflective of such a man, one who was conversant with and adept at designing in a wide range of historical styles fashionable with the Beax-Arts Classicists of his era. It seems that it was precisely because of his worldliness, particularly his travels and studies abroad, that he successfully absorbed and assimilated ideas that later provided important sources for artistic inspiration.

Kimballs' achievements, though always traditional, with historically correct references to the past rather than radical inventions in modernist form, won him national recognition. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to the first National Fine Arts Commission in 1909, and he was chosen by his peers to be President of the American Institute of Architects from 1918 to 1920.

Thomas Rogers Kimball died September 7, 1934 and is buried at Omaha's Forest Lawn Cemetery.

~The Beauty of Thy House, 2005